Master pistolsmith Terry Tussey presents a sub-Officer’s 1911 with seven rounds of payload in a super compact package.

Bridging a chasm some 2,000 years wide, master pistolsmith Terry Tussey has melded one of the oldest metallurgical processes for making weapons with completely state-of-the-art modern manufacturing methods to create a subminiature .45 that is as distinctive in appearance as it is innovative in construction.

The damascus slide on Tussey’s custom Caspian Arms pistol harkens back to the Hittites who, around 1,500 BC, were the first people to discover that iron reduces from “red earth,” iron ochre. Ancient blacksmiths heated the iron ore and then hammered out iron spears and swords. Later, blacksmiths learned to hammer different compounds into the blades, adding phosphorus and using acids to treat the resulting steel. Known as “pattern welded,” the technique for making damascene steel spread throughout the world, responsible for everything from double-edged Viking broadswords to fearsome katana blades of the Japanese samurai.

The advantage of damascus was that it allowed the blade to be both strong and flexible. The Japanese were particularly skilled at carbonizing the edge to make it extremely tough.

Damascene was applied to firearms in the 17th and 18th centuries, appearing first in Arabia. The barrel was pattern welded by winding a damascened band in a spiral around a mandrel. Some beautiful damascus gun barrels were made as blacksmiths intertwined the contrasting colors of iron into artistic patterns.

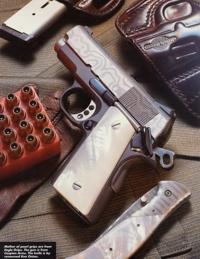

Today, Caspian Arms offers a damascus 1911 slide made by a steel mill in Sweden called Damasteel. Damasteel pioneered a modern method of damascene using a patented proprietary process. Damasteel laminates two carbon steels together that are repeatedly folded and welded, up to 112 layers thick. The steel is then twisted, rolled, forged or machined to give it a distinctive “Damascus” look. Every pattern is distinct and individual, which is only appropriate when a custom pistolsmith of Tussey’s talent applies his craft.

Mated to the damascus slide is a Tussey-designed frame that he spec’d for Caspian Arms. Called the Compact, it’s 1/2″ shorter in the grip and 3/8″ shorter in length than an Officer’s frame, yet holds a payload of 6+1 rounds of .45 ACP. The frame on our test gun is aluminum but incorporates a clever, Tussey-designed steel feed ramp to prevent sharp-nosed hollowpoints from damaging the aluminum.

Tussey’s frame, combined with a shortened damascus slide, results in a very small carry gun, light and highly concealable, yet stylish enough to create enormous pride of ownership.

Old School Smith

Tussey is an old school pistolsmith, a one-man-shop practitioner who still zeros every gun he builds himself. “I bought a .45 when I was 17-years-old after reading Cooper’s Fighting Handguns. I already had a lathe at home and I started working on triggers. I got hired by [Los Angeles gunshop owner] Martin B. Retting in late ’59 and that was my first paid job working on guns. I’ve actually done trigger work and part-time gunsmithing ever since,” said the veteran customizer.

Tussey worked as a sales rep for Safariland and Colt during the ’60s and ’70s to supplement his gunsmithing sideline. “In ’79, I gave up all the extra stuff and went strictly into building custom pistols, kinda forced out by telemarketing. My middle daughter took over my route selling guns while I made the transition. She did it for no pay, just to help the family out,” said Tussey, a father of four and grandfather of nine.

“I haven’t caught up since 1981. Three to six months is the backlog,” he added with a wry smile.

Miniature Tradition

Tussey calls this little pocket pistol his “Deep Cover” model. It’s a small gun, “chopped and channeled” in the classic tradition. Cut-down automatics were the definitive “custom” pistols of 20 years ago when names like Behlert, Devel, Seecamp and ASP were shrinking down full-size service pistols into diminutive, discrete carry guns before the word “compact” had ever been uttered by a major manufacturer.

Charlie Kelsey, the mastermind behind the Devel Corp., abbreviated the Smith & Wesson Model 39 and 59 down to Lilliputian dimensions. ASP did similar work, although not nearly as tastefully, while Austin Behlert offered a remarkably fine cut-down Browning Hi-Power. Seecamp shrank the Colt Commander to a Bobcat.

The factories eventually smelled the coffee and guns like the Smith & Wesson Model 3913, Kahr and Kel-Tech were introduced. With the factories imitating art, demand for custom chop jobs all but disappeared; Devel, ASP and Behlert soon were out of business.

Still, the lure of the hacksaw runs strong. It wasn’t long before “compact” wasn’t small enough; “ultra compact” was the hot ticket. Believing smaller is better, pistolsmith Bill Laughridge pioneered a sub-Officer’s sized Colt while he was working as a consultant for Colt, a gun he called the Adventurer. The Adventurer eventually came out of Hartford as a production gun known as the Defender.

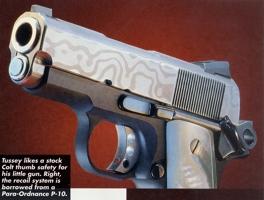

Tussey, meanwhile, was developing the Deep Cover, which compares favorably to the other sub-compacts on the market. It is smaller than a P-10 and an Officer’s, but 0.1″ longer in the grip than the Adventurer, however, it holds six rounds in the magazine compared to the Adventurer’s five.

The inspiration for the Deep Cover was Detonics, the first successful manufacturer of micro .45s. “I was screwing around with a Detonics and had a P-10 around and I thought, `I wonder if I can put these two together?’ So with a little judicious hacksaw work,” Tussey chuckled at the memory. “I hacked off the end of the grip and the end of the slide, and it seemed like I was throwing away more weight than I retained.”

Size Matters

Tussey did everything possible to miniaturize the Deep Cover. Note the nubbin of a beavertail. Tussey first handfit an aluminum Caspian Arms beavertail and then expertly ground it down to mate with the frame in a virtually seamless blend. That saved a good 1/2″ of overall length.

“If you sit an Officer’s and the Caspian on a table on their tail, you’ll see a big, big difference. Even with the Para P-10 or the Colt Defender, you’ll see a big difference because of the little beavertail. The gun is almost an inch shorter than an Officer’s, yet the barrel is only 3/8″ shorter than an Officer’s,” Tussey explained.

The sights are even miniatures Novaks borrowed from a Colt Mustang. He shortened the front sight fore and aft to make it match the tiny rear Novak.

The magazine is made for the Detonics, but works perfectly in Tussey’s Deep Cover, holding six rounds. Tussey prefers to run hardball in his personal gun, arguing that hollowpoints won’t reliably expand at less than 1,000 fps velocity.

“Because it has a short barrel, as an Officer’s does, it’s difficult to get a bullet going more than 1,000 fps. Under 1,000 fps, they do not reliably expand. So I recommend using a 230 gr. bullet that doesn’t need to expand. I just use hardball. For legal purposes, I use hardball that’s marked `match,”‘ Tussey said, cognizant as everyone in the gun business is these days of product liability.

Tussey’s belief that hollowpoints “won’t expand” at less than 1,000 fps is somewhat dated. Most of today’s high performance hollowpoints – Federal’s 165 gr. Personal Protection .45 load is a great example- are specifically designed to expand at lower velocities. Shooting editor Charlie Petty has tested numerous .45 ACP hollowpoints that expanded to almost twice their diameter in water at 800 fps.

As a general rule of thumb, you give up 50 fps for each inch of barrel reduction. In this case, the thumb was correct. The snubby .45 gave up almost exactly 100 fps for the same loads tested in a 5″ barrel (see accompanying chart).

Custom Work

While the damascus slide is the first aspect that catches the eye, there is an incredible amount of custom work on the little Caspian .45. “Everything in the whole back end of that gun is custom,” Tussey elaborated. “I actually build up the tang of the frame, especially on a Colt frame, and use the old style Commander grip safety, actually melding it in. I use an aluminum grip safety on custom guns and steel on the Series 80 Colts because aluminum won’t work.”

The beavertail has been seriously abbreviated, ground down to a nubbin. The upside is the gun is seriously small; the downside is I had to wear a leather shooting glove to prevent hammerbite.

For the manner in which I carry a self defense pistol- mostly in a fanny pack, occasionally in a belt holster behind my hip- the extra half-inch of beavertail would not compromise concealment, but it would make the pistol a lot more shootable. As it is, I bleed if I shoot the gun without a glove. Bleeding is not a good thing. Bleeding is something I generally don’t look forward to.

That being said, Tussey didn’t seem to be bothered by shooting the little guy as much as I was. Maybe I force my hand higher on the grip, a habit incurred from years of IPSC.

Tussey makes his own sear spring and mainspring. He utilizes a Seecampdesigned double captive recoil spring that is currently found in other sub-compacts such as the Kahr, Para P-10 and Glock 26/27. The mainspring housing is from a Para P-10.

The underside of the trigger guard has been radically sculpted to raise the hand as high as possible on the pistol. This gives an extra 1/2″ of purchase on the stubby grip, which is important on a midget grip like this.

Gold Cup style serrations are cut on the front strap, although checkering is an option. Tussey prefers the serrations, however, because checkering can tear up jacket or pocket linings.

The barrel is a Bar-Sto, fitted just the way it should be. Tussey is a real stickler for correct barrel fitting and the accuracy of his custom guns show it.

Tussey thinned the mag catch and relieved it so that it’s harder to press inadvertently. He thinned and shortened the slide stop on the starboard side so it doesn’t gouge you when you sit on it. He also recessed the slide stop hole to facilitate pushing the slide stop out.

All corners and edges are tastefully broken, a “carry bevel package” as Tussey calls it. “I used the small thumb safety for the same reason- so it doesn’t gouge you when you carry it next to you, or sit on it,” Tussey said.

The mag well is beveled, a nice but largely academic touch on a gun that will never see the light of an IPSC match. The springs are all from Wolff.

Shooting Test

With a 3″ barrel and a 5″ sight radius, the Tussey chopped.45 is not going to win Camp Perry. I didn’t expect X-ring accuracy and I wasn’t disappointed. The pistol is a 3″ to 4″ gun at 25 yards, hand-held.

I was disappointed with that accuracy and asked our shooting editor, Charlie Petty, to Ransom Rest Tussey’s pistol to see if it was just my flinching. It was. In the Ransom fixture, the Tussey pistol produced an average of 2.56″ for five 10-shoe groups at 25 yards with Federal hardball Average velocity was 766 fps, which is 9( fps slower than the same ammo clocked through a standard 5″ barrel. Petty also shot the Tussey gun by hand and he too reported mediocre accuracy. “The thing is a real miserable bitch to shoot groups with. I wasn’t able to do much better than 4″ either. Recoil really isn’t fun,” Petty reported in an email to me.

“I see this as a step backwards,” Petty continued. “We spent all those years trying to eliminate hammer bite and Tussey goes and cuts off a perfectly good beavertail. I’m sure it’s more concealable, but I would rather have my Seecamp than something that makes me bleed after three shots.”

As noted previously, I wore a shooting glove to prevent lacerating the web of my palm due to the nonexistent tang. What with brass zinging off my forehead and the slide trying to cut me, this gun was not what I would term “shooter friendly.” Small, yes, fun to shoot, no.

Petty praised Tussey’s workmanship: “Nice work on the barrel fitting, too, and it shows. Excellent accuracy for hardball.”

The little damascus pistol displayed an annoying, nay painful, tendency to throw brass straight back into my face. This is due to the fact that the ejector is too short for the cyclic rate of the little beast.

Reliability was excellent. Neither Petty nor I experienced any jams.

Holsters for the Deep Cover aren’t a problem- anything that fits a Para P10 or Colt Defender works perfectly. Even an Officer’s holster will work, although there’ll be an extra 1/2″ of leather at the muzzle.

The trigger was astonishingly crisp and light- far too light, in my opinion, for a carry gun. Tussey was obviously trying to impress me with his ability to set a 2 lb. trigger. Nothing against light triggers on a competition gun, but on a street gun, you really want at least 3 if not 4 lbs.

Whoa, wait a second. I tested the Tussey trigger and it weighed exactly, right on the money, 4 lbs. on a Brownells’ trigger gauge. What’s up with this? Tussey chuckled, “You thought it was lighter than four pounds, didn’t you?” I admitted it. “That’s the way my triggers feel. They’re crisp and smooth, but they’re not light,” Tussey explained. I was impressed.

Impressive, in fact, is a good adjective for this distinctive damascus slide Caspian custom pistol. It’s certainly eye-catching and Tussey’s custom work is absolutely top-notch. Tussey, in his early 60s, is at the pinnacle of his pistolsmithing career, producing carry guns of the highest order. I would not, however, make the Deep Cover my first choice from his catalog of offerings unless concealability was my over-riding consideration. I would prefer a bit more size and a little less stealth in exchange for a pistol that’s more conducive to shooting.

Damascus Knight .45

By Cameron Hopkins

HANDGUNNER Magazine

July/August 2000